Rome owed her rise to the fighting qualities of her peasant-proprietors. The traditional picture of the earliest republic and the struggle between the orders clearly show that then already the normal Roman was a landowner. It is true that the distress of the plebeians indicates that their plots must often have been very small, and it is also true that, according to modern archaeological theories, there had probably existed, before recorded history begins, in Latium generally, as in Etruria, a system of villeinage, i.e. that the bulk of the population had been semi-free tenants working on large estates owned by great landlords. But what we know of the economic side of the struggle between the orders is sufficient to show that this state of affairs was over when that struggle took place. One of the chief complaints of the plebeians is that they are forced to serve as soldiers and that on their return from a campaign they find their land ruined through lack of attention, or worse still actually devastated by the enemy, and that they are thus forced to borrow from the larger landowners in order to begin again. This is not the sort of complaint which would be made by a semi-free tenant, whose lord would have the responsibility for setting him up again. The cry too is that the patricians monopolise the advantages of the public lands instead of dividing them up among the poor plebeians, which again shows that the plebeian is capable of holding land and regards such ownership as his normal condition. The "Servian" constitution (whatever be the date that should be assigned to it) also indicates that the normal Roman is a landowner, for its "tribes" are divisions of the land, and probably only landowners are originally enrolled –a procedure which would not have been accepted had there been a great number of landless men, for the arrangement is clearly intended to include the bulk of the population.

If the normal citizen was a small landowner we must not imagine that the estates of the aristocracy were very great either. The tradition of the patricians who had to be called from the plough to lead the armies of the republic probably represents the truth. Rome was a poor and weak state from the expulsion of the kings until at least the time of the capture of Veii (traditional date 396 B.C.), her first great conquest of a foreign people. The earlier part of the struggle between the orders took place during this period of weakness and the main plebeian victory (the Licinio-Sextian laws of 367) was won very early in the period of expansion. The economic provisions among these laws show that Rome was already beginning to go along the disastrous path of large estates and slave labour. One law limited the amount of public land which could be occupied by any individual to 500 iugera, and another laid down that landlords must employ a certain proportion of free labourers. But these measures themselves, though they were not strictly enforced, at any rate after the first few years, must have done something towards remedying the evils at which they were aimed, and still more was done to help the peasants by the use which Rome made of her conquests. After the capture of Veii the city was razed to the ground and her territory divided among the citizens of Rome in equal lots, the plebeians having their fair share, and subsequently Rome made many "assignations" of conquered territory to individuals in addiction to sending out colonies, which, besides their military function, served the purpose of providing land (in very small lots generally) for her increasing body of citizens.

The result of this policy was a population consisting chiefly of a homogeneous race of peasant-proprietors, men "with a stake in the country", who were patriotic enough, hardy enough and numerous enough to provide the relatively very large armies which enabled Rome to continue her career of conquest once it was begun. These peasants tilled their land themselves with the help of their families and in some cases of one or two slaves or persons in mancipio. Commerce and industry seem to have played a comparatively small part in the early development of Rome, and the government was, as we have seen, aristocratic. The success of the plebeians in their contest with the patricians did not change matters; it merely replaced the ancient aristocracy, which had a legal monopoly of office, by a new one in which, though every citizen had equal rights before the law, a comparatively few families, plebeian now as well as patrician, in fact furnished nearly all the magistrates and retained its power through the senate. The aristocracy thus evolved was probably the most successful the world has ever seen. It was not brilliant, and great statesmen were rare, but, like the rest of the Roman people, it was characterised by deep devotion to the state, a steadiness to accept responsibility which made it possible to entrust the great powers of the curule magistracies to a succession of ordinary aristocrats, and thus build up a governing body of men with wide experience of public functions. The Romans had the same fondness for entrusting great powers to individuals which is shown by the English and, like the English, they took a sort of pride in the eccentric use of power; M. Livius, who when censor in 204 B.C. disfranchised thirty-four out of the thirty-five tribes because they had first condemned him in spite of his innocence and then elected him consul and censor, would have precipitated a revolution in most countries.

A great change, both in the external conditions of life and in the spirit of the country, began with the ending of the second Punic war. In seventeen years of continuous warfore the fairest districts had been ravaged, enormous numbers of men had fallen and the whole manhood of the country had been demoralised by continued military life. Agriculture suffered, not only from devastation and lack of the cultivators who were called away on military service, but from competition with the corn which was now imported in great masses from Sicily. Worst of all, the peasant-proprietor was gradually giving way to the great landlord who cultivated his estate mainly by slave labour. The wars enriched the aristocracy who were able to make great sums out of booty and out of the government of the conquered peoples and they also enriched tax-farmers and business men who found new fields for their enterprise. In Italy, as a result of war and confiscation, large tracts of country were acquired by the Roman state, and now that the number of citizens no longer sufficed to cover them with peasant settlements, the only profitable method of exploitation was to let the land in large blocks to people with money, or to continue the old Roman custom of allowing them to "occupy" it, i.e. simply take it informally and thus come under an obligation to pay the state a proportion of the produce. Everything favoured the capitalist. The successful wars made it possible for him to get as many slaves as he liked, and slaves were not only cheaper than free labour but there was no danger of their being called away for military service. Much land was suitable only for use as pasture, and pasture does not pay unless it is managed on a large scale, for a few herdsmen can look after a great number of cattle. On the other hand, competition with the corn-growing provinces was making the fertile parts of Italy turn more and more to wine and olive growing, both of which need capital, for the small man cannot afford to wait the five years before vines or the fifteen years before olive trees will bear. The capitalist therefore tended to absorb the new land and to buy up the peasant-proprietor, who might of course settle in a colony, or go abroad to the provinces as a business man, but who might also drift to Rome and become a more or less idle proletarian living largely on the corn imported from the provinces which the government now already began to distribute, not yet for nothing, but at very low prices. In the second century B.C. there were, no doubt, still large numbers of peasant-proprietors, and it was these men who conquered the East as they had conquered Hannibal, but the process of concentration of the land in fewer hands was going on all the time and was to be largely instrumental in bringing about the revolution. Latifundia perdidere Italiam: "The great estates ruined Italy".

That the wealth which flowed to Rome from her conquest of the East had the effect of corrupting her population is an old and true story. Contact with the East meant contact with decadent Hellenism, and wealth gave the opportunity of copying Hellenistic vices. But with wealth and vice come more desirable things –literature, art and philosophy–. The state, the family and the farm had been the only things that mattered to the old-fashioned Roman; now he saw that there might be more in life. In the third and second centuries B.C. the upper classes became permeated by Greek culture; Greek literature became the basis of education and Greek rhetoric already began to exercise its dangerous fascination over Roman minds. For speculative philosophy the practical Roma had little taste, but the great days of Greek speculation were over and emphasis was already laid rather on the ethical than on the metaphysical side of philosophical teaching. This was true of all the three chief systems, the "new Academy" and Epicureanism as well as Stoicism, but it was Stoicism which found the most favour at Rome. In the first place its speculative system left a place for the gods and their worship, whereas the Epicureans taught that the gods, if they existed at all, had no concern with the lives of men, and it thus did not come into conflict with that religion of the state which the Romans cherished from patriotic motives, even when they did not believe in it. But above all the Stoic ethic, with its ideal of the perfectly wise man who masters his passions in order to live the "life in accordance with nature", appealed to the Roman sense of duty and gave a theoretical justification for that service of the state which had been the guiding principle in the city's life.

The decay of agriculture in Italy and the consequent growth of a landless proletariate, together with the increasing differences in wealth brought about by the new opportunities of acquiring a fortune, of which naturally only a minority were able to avail themselves, were the causes which led to the attempted reforms of the Gracchi (133-121 B.C.) and to the revolutionary period which was to last a century, and then only and in the establishment of the empire. This period presents a number of the most astonishing contrasts. From the point of view of the governmental system it was a time of breakdown, occasionally anarchy, and from that of the governing class of moral decay, and yet it was the most brilliant epoch of Roman history. Foreign conquest did not cease, literature reached a standard never approached before and equalled only by the immediately succeeding period under Augustus, a series of brilliant personalities from Gaius Gracchus to Augustus himself passes across the stage of history, and in the latter years, when civil war was imminent or actually raging, the whole scene is lit up for us, not merely by professional historians, but by the literary genius of two men who were themselves among the chief actors in the drama –Caesar and Cicero–. Though the lawyer finds his "classical age" in the more orderly, if duller, times of the early empire, it is the last century of the republic which is "classical" for the student of language and literature.

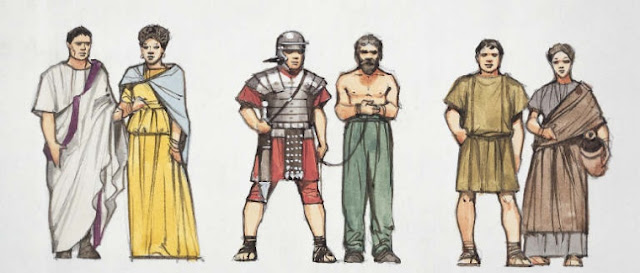

It is, of course, impossible to classify exhaustively all the different orders of men who went to make up what had become a vast and highly civilised state, almost as complex in its social and economic structure as those of modern Europe. We can, however, roughly classify as follows:

- The senatorial nobility

Office was almost exclusively confined to the nobility, that is to say to members of families who could count curule magistrates among their ancestors, though from time to time a novus homo might, by his ability, force his way into the privileged circle. A young man of this class who, as was nearly always the case, was destined for a public career, would as a rule spend some years in military service, though this was apparently no longer legally necessary at the end of the republic. He would then start on his cursus honorum (career of office) by holding one of the magistracies which formed the XXVI virate and, on election to the quaestorship, would become a member of the senate for life. The offices had to be held in order; the praetorship might not be held before the quaestorship, nor the consulship before the praetorship, and a minimum age was laid down for each. For the quaestorship this had been twenty-eight; in Cicero's time it was thirty; for the consulship it was forty-three. Between these two offices there were not only the other offices –aedileship, praetorship, and, for plebeians, tribunate– but service in the provinces, and the rule was that two years must elapse between the tenure of two "patrician" offices. Not before the lapse of ten years might the same office be held again.

The exercise of any trade or profession was a disqualification for office and the senators had thus necessarily to be men of wealth. They were, in fact, all large landowners, often owning several estates in Italy and in the provinces. From direct participation in business, senators had long been excluded by a lex Claudia of 218 B.C., which prevented them and their sons from owning a sea-going ship except for the transport of the produce of their own lands, and probably also forbade them to participate in the acceptance of contracts for the farming of state revenues. In any case, all types of speculative business were regarded as unbecoming to a senator and could only be indulged in secretly, if at all.

By the end of the republic the senatorial nobility was unworthy of the position it held in the state. Cicero, champion of the "order" though he is, inveighs against the degenerates who loll at ease in their villas and care more for their fishponds than for their public duties. The craze for luxury caused many of the aristocracy to run into debt, and the unfortunate provincials had to find enough money, not only to repair the shattered fortunes of their governors, but also to bribe the juries when the governor was prosecuted for extortion on his return. At the height of her power Roma was, in fact, the prey of a degenerate governing class and it needed the strong hand of a monarch to reduce the turbulent nobles to order.

- Equites

The "knights" had become by the end of the republic a second order in the state consisting of wealthy persons, especially publicani. The exact history of their rise is a matter of dispute, but the main facts are these. According to the "Servian" constitution there were eighteen centuries of equites who formed the cavalry of the army, as the remainder of the centuries were the infantry. For these equestrian centuries there was probably no fixed property qualification, but they no doubt consisted of well-to-do people in the first class, for they took precedence in voting over the other centuries. They were known as equites equo publico, because the money for the purchase and upkeep of their horses was provided out of public funds, in fact by unmarried women and orphans with property, who could not appear in the census-list, and made this contribution to the public need instead. Possession of a "public horse" was not originally incompatible with a seat in the senate, and in the earlier republic many senators no doubt remained in the cavalry as long as their age permitted.

In the later republic, however, a knight was bound to give up his horse on entering the senate, and the ranks of the equites appear to have been filled mainly with young men of good family. They did not at this time serve as a corps, the cavalry of the army being drawn mostly from the "allies", but were used as officers on the staff of generals and in other positions of trust. In any case these equites did not form a separate order of society.

As early, however, as the siege of Veii, we hear of equites equo privato, i.e. those who provided their horses at their own expense. Such people would, of course, have to be comparatively wealthy, but we know of no definite qualification.

The important step of making the equites a separate order was taken when C. Gracchus transferred to them from the senators the duty of sitting as jurymen in the courts, especially in that which tried cases of extortion. Mommsen was of opinion that the equites concerned were only the 1800 who had the "public horse", but is considered more probable by most authorities that other equites were included. Very likely it was Gracchus who first laid down the equestrian census of 400,000 sesterces which we find in existence at the beginning of the empire, but, in any case, from his time onwards, the knights became a class of wealthy business men, and seeing that the chief activity of great capitalists at Rome was the undertaking of state contracts, their interests were largely identified with those of the publicani. In many respects their ordo had interests divergent from those of the senatorial nobility who were debarred from participation in business, and it was the object of Gracchus to enhance the antagonism between the two classes in order to further his attack upon senatorial privilege.

The equites, like the senators, had certain outward signs of rank; they wore the angustus clavus, i.e. narrow purple stripes on the tunic (whereas senators wore broad stripes); they obtained the right to the gold ring, which in earlier times had been a senatorial privilege, and they also had special seats allotted to them in the theatre.

Under the empire the equestrian nobility became even more important; admission to it was a necessary first step to any public career, civil or military, for others than the sons of senators, and many very important posts were confined to men of equestrian rank, to the exclusion of senators.

- The middle and lower classes

Among these we must reckon all free persons who did not belong either to the senatorial or equestrian orders. In the last centuries of the republic, in spite of the anarchical state of the government, Italy appears to have been prosperous. In the growing cities there were business men wealthy enough to build themselves elegant houses, and many others living on the income brought them by estates of moderate size, worked, like the great ones of the senators, mainly by slave labour. Among this well-to-do municipal aristocracy, from which the local magistracies were filled, must also be reckoned some of the ex-soldiers who were given plots of land on their discharge. We know, for instance, that a number of Sulla's veterans were settled at Pompeii and became the leading element in the population.

In the country the free peasantry was certainly not extinct, and though many suffered from the loss of their holdings as a result of confiscation in the civil wars, their places were taken by the veterans settled on the land by the military leaders. There must also have been considerable numbers of free tenants of the landlords, though in the main cultivation was done by slaves. These tenants were not independent people like the English tenant-farmer, working lands in much the same way as an owner and finding their own markets for their produce, but quite small men forming part of the larger economic unit constituted by the estate as a whole, and very closely dependent on the landlord.

In the cities there was no great class to correspond with the mass of working-men in a modern industrial state, first because most of the corresponding work was done by slaves, and secondly because industry in the ancient world never developed to the extent to which it has grown in the modern. But there were, of course, numbers of artisans, some working in small shops, which made goods to order for customers, and others making standard articles for an indefinite market. The factory system, however, did not prevail to any great extent; most of the articles appear to have been made in small shops and distributed though business men who bought them from the makers; Roman industry never played such a large part in producing great fortunes as did commerce.

The greater part of the working-classes were, however, not free men but slaves, of whom great masses worked on the estates, great and small, and in the workshops of the cities. The status of all these men was legally identical; they were owned like any other piece of property by their masters, but in practice their positions varied very greatly, from the farm-labourer who was often forced to work in chains, who slept in a sort of barracks and was excluded from all possibility of family life, to the slave-bailiff in charge of a great estate owned by an absentee landlord, or the confidential secretary of a Roman of high rank who might, like Cicero's slave, Tiro, become a "humble friend" of the family. Often a man would appoint his slave manager of a business, in which case he acquired the profits but became liable in full on contracts made in connection with the business. Otherwise, apart from authorisation, he could not be sued on his slave's contract for an amount greater than the peculium, i.e. the property which, though it remained legally the master's, the slave was permitted to administer for himself. As the master could appropriate any gains that accrued, he stood to profit without restriction, though his liability was limited.

These better-placed slaves were often allowed by their masters to accumulate money in their peculia and purchase their own freedom with their savings, that is to say the master would agree (though such an agreement would not be enforceable at law) that if the slave saved a certain sum he would take that sum and manumit the slave. Such an arrangement naturally acted as a powerful inducement to the slave to work hard. Many slaves were also manumitted from motives of liberality, or indeed of ostentation. This last motive applied particularly to manumissions by will, for the Romans were much addicted to funereal pomp, and it made a good impression if a large number of grateful freedmen followed a man in his last procession.

The social and political importance of this practice of manumission was very great indeed, especially as Roman law, more generous in this respect than the Greek systems, gave to the manumitted slave (provided the proper formalities were fulfilled) not only complete freedom but citizenship. The result was that from the time when slaves began to be numerous a great part of the citizen population was of servile birth, and, what is still more important, of foreign race, for most of the slaves were prisoners captured in war. Greeks and other races of the Eastern Mediterranean especially mingled their stock with that of Italy in this way, for they had the civilisation which fitted them for the better positions, while the Gauls, for instance, were mostly used for hard physical labour in the fields or mines and had little chance of manumission.

The freeman (libertinus), although a citizen, was not on an entire equality with the free-born man as regards political rights. He had a vote, but as all freedmen were confined (except for short periods when democratic leaders succeeded in passing laws removing the restriction) to the four "city" tribes, there were thirty-one out of the thirty-five tribes which he could not influence. From voting in the centuriate assembly he was no doubt originally excluded, for, throughout the republic, freedmen might not serve in the legions (though regularly used for the less honourable service in the fleet), but when the comitia centuriata ceased to have any close connection with the army and was based to some extent on tribal divisions freedmen were probably included. For magistracies and the senate freedmen were not eligible.

In spite of their political disabilities freedmen formed a very important class of the population. Most of them came of quick-witted races and it was naturally the most intelligent that secured their freedom, though a youth passed in the abominable condition of slavery did not tend to make them too scrupulous. They congregated mostly in the towns, where they probably made up the larger part of the free working population. Some, no doubt, became rich, though we do not yet hear of the colossal fortunes which became proverbial in the early empire.

Particular importance attaches to the proletariate in Rome itself. Now that the citizen body was spread all over Italy it was, of course, impossible for the great majority of voters to attend the assembly except very occasionally. Numbers of out-voters came for the consular elections in the summer, but legislation was practically in the hands of those who happened to reside in Rome. It must be remembered that the comitia remained throughout a primary assembly; the device of representative government was never adopted. Anyone therefore who could keep the populace in the city in a good temper had in his hands the legislative organ of the Roman state. The chief means adopted for this purpose was the distribution of corn by the state at very low prices, a practice which had begun under C. Gracchus. In Cicero's time every citizen who applied received a ration equal to that of the soldier for about one-third of the market price. These distributions were made at the expense of the state, but there were other advantages which came out of private pockets, especially the costly games which an aspirant to the higher magistracies was almost forced to provide if he did not want to receive an unpleasant check to his career.

The result was naturally that the plebs urbana degenerated and that the comitia became merely a machine for registering the wishes of the man who could obtain the greatest popularity at the moment or could bring an army to overawe the population.

This last proceeding would, of course, have been quite inconceivable in the earlier republic when the army was almost identical with the population, but a momentous change had taken place. Under the older system military service was compulsory and based on a property qualification: the capite censi had not been liable. In the third and second centuries B.C. owing to wars, and emigration to the provinces, the number of citizens and especially (owing to the growth of latifundia) of citizens with the requisite amount of property decreased, and military service also became unpopular with the well-to-do classes. On the other hand there were a number of unpropertied citizens who were only too glad to have a livehood provided for them in the army and resented their discharge at the end of a campaign. Successive lowering of the census required for enrolment did not meet the case and the final step had to be taken in 107 B.C. after a crushing defeat by the Gauls had annihilated a whole army. Marius, then consul, and one of the greatest of Roman soldiers, opened the ranks to all citizens who cared to enlist, irrespective of any property qualification. The result was that the Roman army became a mercenary one. The soldier was a professional; his interests lay with the army and not with the state as a whole, and his loyalty was for the general who led him and on whose good offices he depended for an allotment of land when his time of service was over. It thus became possible for Roman generals to use their armies as instruments for working their will upon the state, and this power, once realised, led through the long agony of the civil war to the establishment of the military autocracy that we call the empire.

----------

Source:

Historical introduction to the study of Roman law, H. F. Jolowicz, pages 72 - 82.